Joni Mitchell : interview on creativity

She revisits this notion of creating from a place of freedom rather than normative restriction based on the ideals and shoulds of others:

Mitchell's creative source springs from precisely this feeling of miraculous, wholehearted aliveness. She tells Marom:Freedom to me is a luxury of being able to follow the path of the heart, to keep the magic in your life. Freedom is necessary for me in order to create, and if I cannot create I don’t feel alive.

Much of what we call "inspiration," Mitchell suggests, is really the active practice of finding oneself by getting lost:How does a person create a song? A lot of it is being open, I think, to encounter and to, in a way, be in touch with the miraculous.

I think that as long as you still have questions, the child questions, the muse has got to be there. You throw a question up to the muse and maybe they drop something back on you.

'In the Park of the Golden Buddha,' 1995

When Maron notes that "once you’ve known poverty, it digs into you no matter how successful," Mitchell agrees and admits to being "suspicious of wealth" because she had come from destitution. Looking back on that tipping point when she went from struggling artist to star, with the affluent lifestyle to boot, she contemplates the inner tussle of values:

I had difficulty at one point accepting my affluence, and my success, even the expression of it seemed to me distasteful at one time, like to suddenly be driving a fancy car. I had a lot of soul searching to do. I felt that living in elegance and luxury cancelled creativity, or even some of that sort of Sunday school philosophy that luxury comes as a guest and then becomes the master. That was a philosophy that I held onto. I still had that stereotyped idea that success would deter it, that luxury would make you too comfortable and complacent and that the gift would suffer from it.

But I found that I was able to express it in the work, even at the time when it was distasteful to me... The only way that I could reconcile with myself and my art was to say, “This is what I’m going through now; my life is changing. I show up at the gig in a big limousine and that’s a fact of life.”I’m an extremist as far as lifestyle goes. I need to live simply and primitively sometimes, at least for short periods of the year, in order to keep in touch with something more basic. But I have come to be able to finally enjoy my success, and to use it as a form of self-expression.Leonard Cohen has a line that says, “Do not dress in those rags for me, / I know you are not poor.” When I heard that line, I thought to myself that I had been denying, which was hypocritical. I had been denying, just as that line in that song, I had played down my wealth.Many people in the rock business [have] their patched jeans and their Levi jackets, which is a comfortable way to dress, but also it’s a way of keeping yourself aligned with your audience. For instance, if you were to show up at a rock and roll concert dressed in gold lamé and all of your audience was in Salvation Army discards, you would feel like a person apart.

Leonard Cohen and Joni at the 1967 Newport Folk Festival

Despite how gradual her rise had been and how emblematic of the idea that the myth of the overnight success is indeed a myth,

Mitchell recalls the hollowing feeling of beginning to feel separate

from her audience by a magnitude of wealth. And yet she finds her peace

in a rather Zen-inspired perspective, one where everything that is is

welcome as it is, allowing experience to unfold without the layering of

judgment. Seen that way, poverty and affluence, like meeting and separation

and like most seeming polarities in life, are two sides of the same

coin, two dimensions of the human experience, riddled with many of the

same anguishes and anxieties. (Henry Miller touched on this beautifully

in his 1935 meditation on money, through the parable of the factory owner's predicament.) Mitchell tells Marom:Echoing Georgia O'Keeffe's ideas on mental toughness, she adds:I’m still searching for meaning and purpose. You know, people have a funny idea that success, [that] luxury is the end of the road. That’s not the end at all. As a matter of fact, many troubles begin there. They’re just of a different nature.

I’ve had the experience of poverty, middle class, now extreme wealth and luxury, and that’s difficult too.

But her most eloquent and sensitive articulation of these ideas, fittingly, comes from one of her songs – "The Boho Dance" from her 1976 album The Hissing of Summer Lawns:I live in a beautiful place, like it would be a dream place. Many a day I walk through it and don’t see anything... If I have to live with less, I can do it easily. I can live with much less. As a matter of fact, for my nature, it’s too complicated to have so much because I can never find anything. [laughs] That’s a silly little problem but you don’t need that much. It’s a big headache... I like the luxury of having a swimming pool. But if I could have a shack or a tent down there next to my swimming pool, I’d be very contented. [laughs]

a>

a>Joni Mitchell: In Her Own Words is a magnificent read in its entirety – a rare glimpse into the inner world of a rare kind of genius. Complement it with Leonard Cohen on the key to the creative life, Bob Dylan on sacrifice and the unconscious mind, Pete Seeger on the myth of originality, and Carole King on overcoming creative block.You read those books where luxury

Comes as a guest to take a slaveBooks where artists in noble povertyGo like virgins to the graveDon’t you get sensitive on me’Cause I know you’re just too proudYou couldn’t step outside the Boho dance nowEven if good fortune allowedLike a priest with a pornographic watchLooking and longing on the slySure it’s stricken from your uniformBut you can’t get it out of your eyes

:: MORE / SHARE ::

http://www.brainpickings.org/

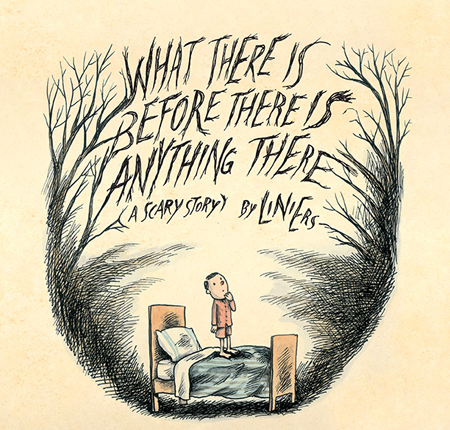

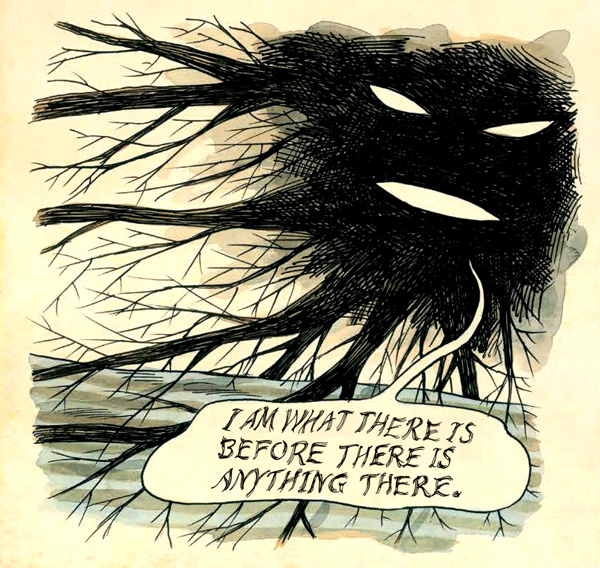

What There Is Before There Is Anything There: Celebrated Cartoonist Liniers Confronts Childhood Nightmares

By: Maria Popova

An imaginative graphic novel about the quintessential childhood fear.

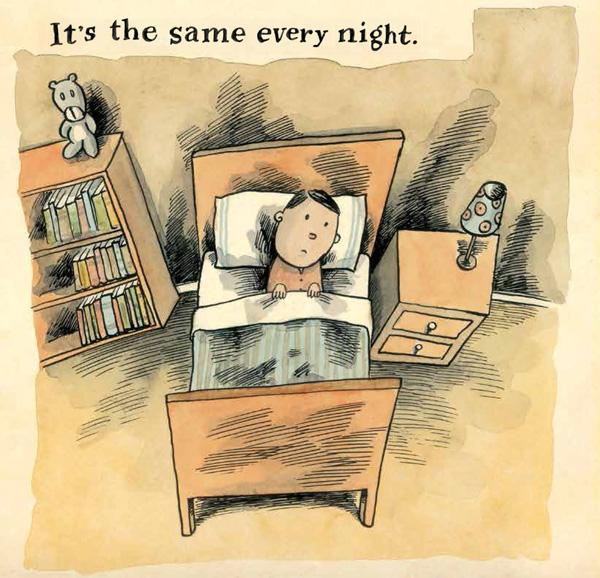

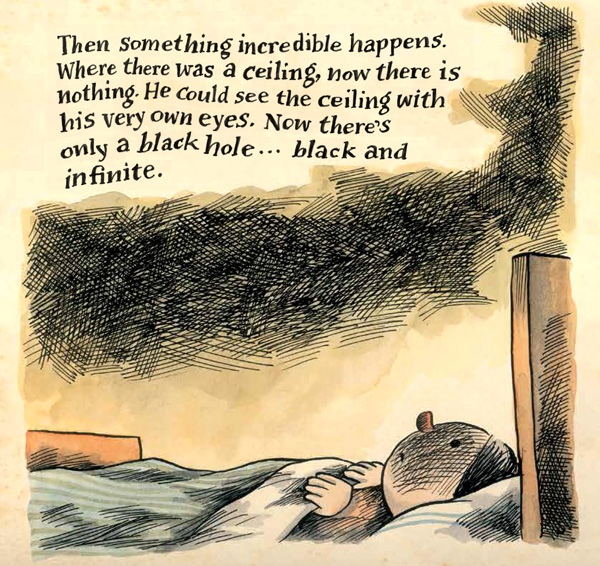

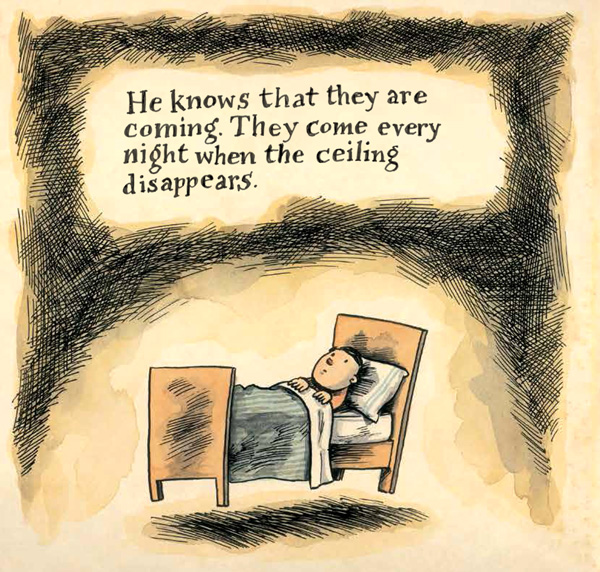

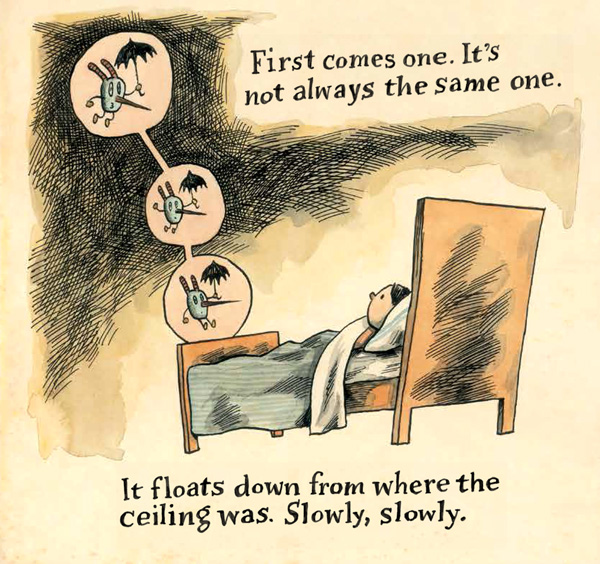

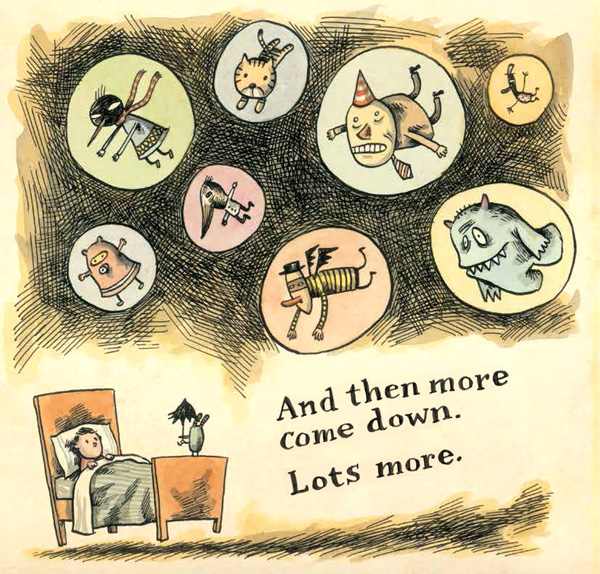

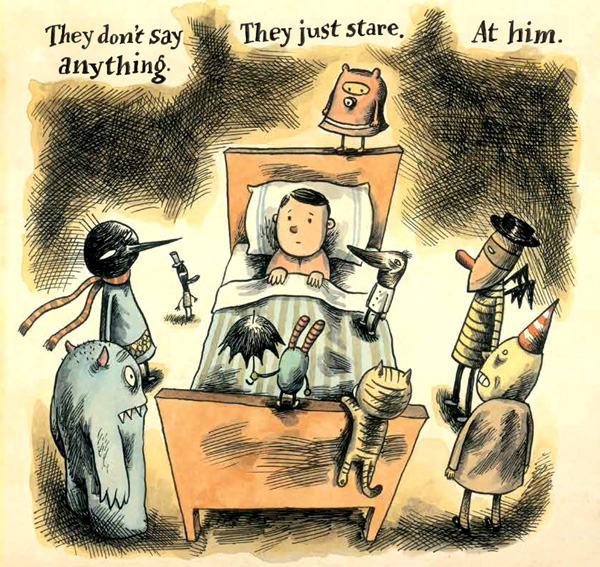

Children often wonder about why we dream, as do some dedicated researchers, but the question of why we have nightmares

is as perplexing to scientists — some of humanity’s most intelligent

grownups — as it is exasperating to kids. Indeed, nightmares, along with

its sister fear of the dark, are among childhood’s most anguishing and

common experiences, as exasperating to the child experiencing them as to

his or her parents in their helplessness of assuaging them.

Children often wonder about why we dream, as do some dedicated researchers, but the question of why we have nightmares

is as perplexing to scientists — some of humanity’s most intelligent

grownups — as it is exasperating to kids. Indeed, nightmares, along with

its sister fear of the dark, are among childhood’s most anguishing and

common experiences, as exasperating to the child experiencing them as to

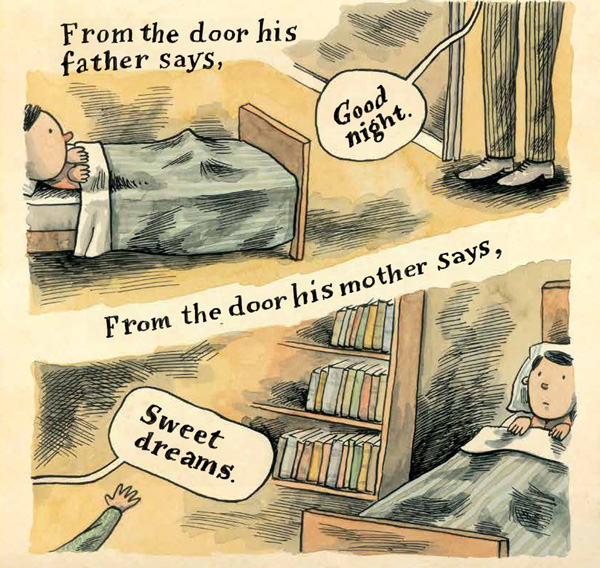

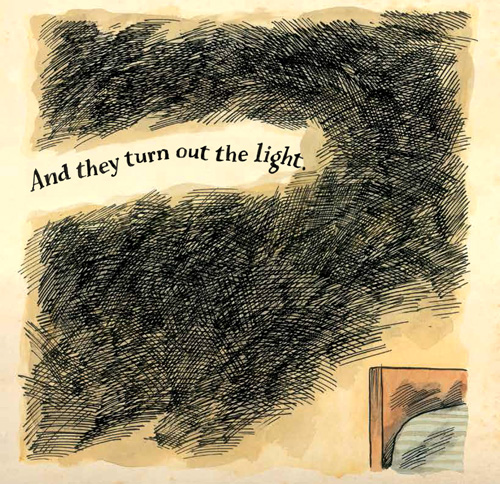

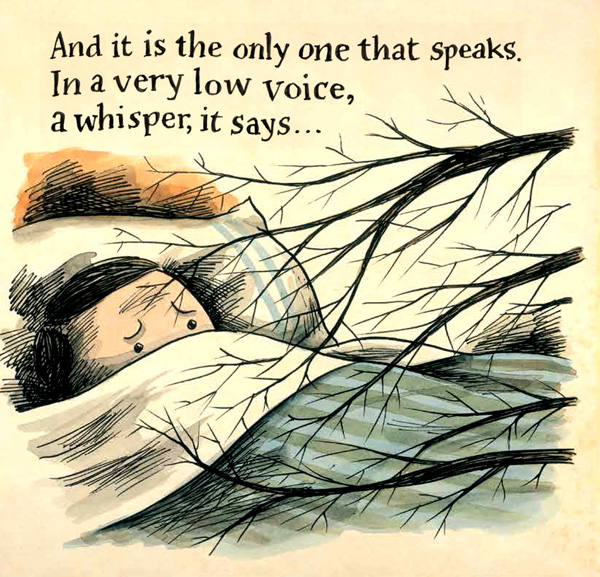

his or her parents in their helplessness of assuaging them.That’s precisely what award-winning Argentinian cartoonist and New Yorker cover artist Liniers (whose beloved Macanudo series was just released in English for the first time) explores in What There Is Before There Is Anything There: A Scary Story (public library) — a wonderful picture-book that brings dark humor to those familiar nighttime fears while taking them seriously, at once spooky and sweet in its solidarity of acknowledging that they are very much real, even if their objects are not true. One of the great injustices of childhood, after all, is the recurring experience of not being believed by grownups, not being validated in one’s fears and fancies and subjective truths simply because one is a child. Liniers refuses to negate the realness of those childhood fears and instead meets them with equal parts reassurance, imagination, and gentle wit, in a style reminiscent of Edward Gorey yet distinctively his own.

What There Is Before There Is Anything There, a treat in its delightfully spooky yet assuring totality, is translated by Elisa Amado and comes from Canadian independent picture-book publisher Groundwood Books, who also gave us the enormously heartening Migrant, a kind of Alice in Wonderland for the modern immigrant experience. Complement it with a very different take on the same subject in Lemony Snicket’s The Dark, illustrated by Jon Klassen.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.